Imagine a world without light, without refrigerators, without the devices you're using to read this very sentence. That’s a world without electricity, and a world where the electric generator, in its many forms, is conspicuously absent. For something so fundamental to modern life, understanding the basics of what is an electric generator? can feel surprisingly complex. Yet, at its core, this remarkable machine simply translates motion into power, fueling nearly every aspect of our existence.

Whether providing the juice for our global power grids, offering critical backup power during outages, or even lighting a bicycle path, electric generators are the unsung heroes of our electrified age. They are the essential link, transforming raw energy sources into the usable electrical currents that power our homes, industries, and technological marvels.

At a Glance: Key Takeaways About Electric Generators

- Core Function: Converts mechanical energy (motion) into electrical energy.

- Fundamental Principle: Relies on Michael Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction.

- How They Work: A rotating component (rotor) interacts with a stationary magnetic field (stator) to create an electric current.

- Main Types: Dynamos (produce DC) and Alternators (produce AC), with alternators being dominant for grid power.

- Power Sources: Driven by everything from steam and gas turbines to wind, water, and even human muscle.

- Ubiquitous Use: Found in power stations, vehicles, backup power systems, and portable devices worldwide.

- Essential Maintenance: Regular checks of filters, oil, and connections are vital for reliability and longevity.

The Invisible Force: Unpacking the Generator's Role

At its most fundamental level, an electric generator is an electromechanical device designed to convert mechanical energy into electrical energy. Think of it as a translator: it takes kinetic power – the energy of motion – and speaks it in the language of electricity. This incredible process is responsible for virtually all the electric power that courses through worldwide grids, illuminating our cities and driving our machines.

But how does it manage this transformation? It all boils down to a clever bit of physics. Generators work by rotating a shaft, which in turn causes an electric current to be produced. This current then powers various electrical loads, from the lightbulb in your home to the massive machinery in a factory. Without this elegant conversion, our modern, electrified world simply wouldn't exist.

A Flashback to Discovery: The Genesis of Electric Power

The journey of the electric generator began not with a roar of machinery, but with a quiet observation in a laboratory. The operating principle of electromagnetic generators was first uncovered by the brilliant scientist Michael Faraday in 1831–1832. His groundbreaking work, now famously known as Faraday's law of induction, laid the theoretical bedrock for everything that followed.

Early Innovations: From Faraday's Disk to Dynamos

Faraday wasn't content with just theory; he built the first electromagnetic generator himself. Dubbed the Faraday disk, it was a homopolar generator that, while producing only a small DC voltage, proved the concept. Early designs were far from perfect, often grappling with self-canceling currents and low voltage outputs. However, ingenuity prevailed, and later improvements, such as using multiple turns of wire, slowly boosted their efficiency.

Before Faraday's electromagnetic marvels, other devices like electrostatic generators existed. These could produce high voltages but were extremely inefficient for generating substantial current, limiting their use to specialized applications like X-ray tubes and particle accelerators, rather than commercial power.

The path to practical power generation continued in 1827 with Ányos Jedlik's experiments, which eventually led him to discover the principle of dynamo self-excitation between 1852 and 1854. This innovation was a game-changer, replacing earlier designs that relied solely on permanent magnets. The first truly practical DC generators, known as dynamos, emerged. These early dynamos, exemplified by Hippolyte Pixii's 1832 invention, ingeniously converted alternating current (which was initially produced) into pulsing direct current using a component called a commutator. The Woolrich Electrical Generator, developed in 1844, stands out as the earliest industrial generator, marking a significant step toward practical, large-scale power production.

By 1866-1867, a trio of inventors – Sir Charles Wheatstone, Werner von Siemens, and Samuel Alfred Varley – independently revolutionized the dynamo. Their designs employed self-powering electromagnetic field coils instead of less powerful permanent magnets. This breakthrough dramatically increased power output, paving the way for the electrification era.

The Dawn of AC: Alternators Take Center Stage

While dynamos were making strides, another form of power generation was brewing: alternating current (AC) generators, also known as synchronous generators (SGs). These would eventually succeed dynamos as the primary source of grid power. J. E. H. Gordon was instrumental in this transition, building large two-phase AC generators in 1882.

However, it was William Stanley Jr. who provided the first public demonstration of an "alternator system" in 1886. This showcased the practicality of AC for widespread distribution. A pivotal moment came with Sebastian Ziani de Ferranti's design of the Deptford Power Station in 1887. Completed in 1891, Deptford was the first truly modern power station, capable of supplying high-voltage AC that could then be "stepped down" for safe consumer use. This system of generating high-voltage AC for efficient long-distance transmission, then transforming it to lower voltages near the point of consumption, is the very same principle still widely used today. The introduction of polyphase alternators after 1891 further cemented AC's dominance, allowing for more efficient power delivery to industrial loads.

Anatomy of a Powerhouse: What Makes a Generator Tick?

Understanding how a generator actually creates electricity involves looking inside at its core components. While designs vary, most electromagnetic generators share a few fundamental parts that work in concert.

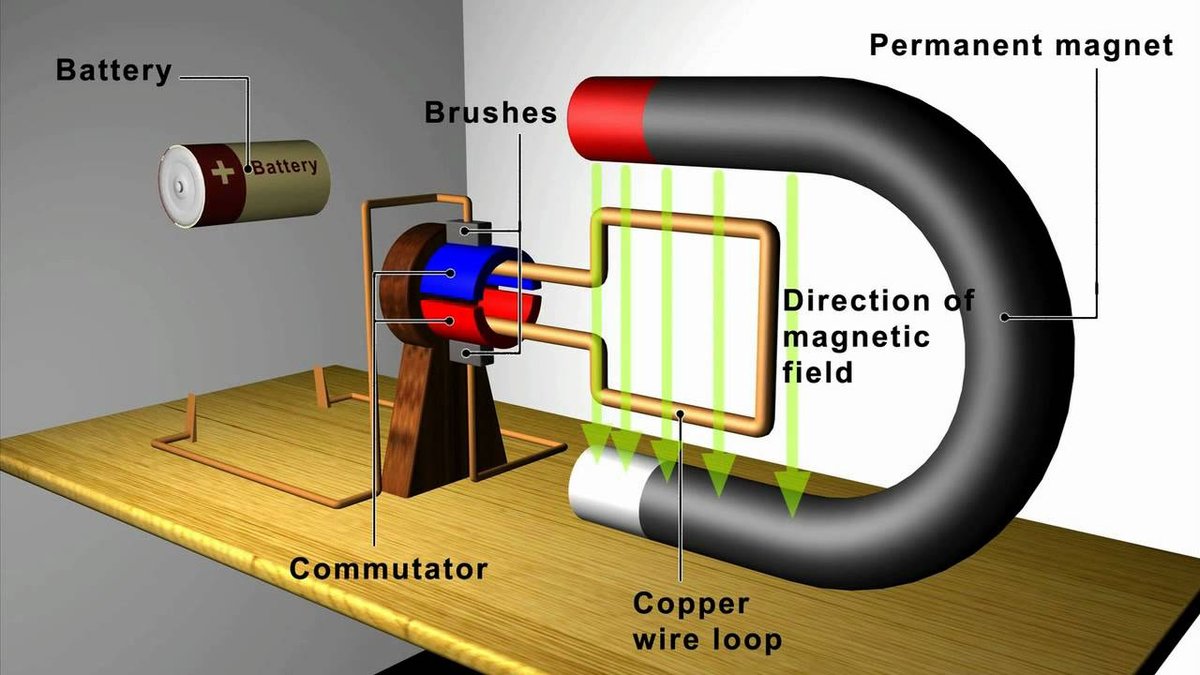

The Moving Parts: Rotor and Stator

Mechanically, a generator consists of two primary sections:

- Rotor: This is the rotating part of the generator. It's the component that gets spun by whatever mechanical power source is driving the generator.

- Stator: This is the stationary part that surrounds the rotor. It provides the framework and often houses critical components that interact with the rotor.

Creating the Spark: Field Windings and Armatures

The magic of electricity generation happens through the interaction of magnetic fields and conductors:

- Field Winding or Field (Permanent) Magnets: This is the component that creates the magnetic field. In some generators, this is achieved by wire coils (field windings) that are energized by a small electric current to become electromagnets. In others, permanent magnets are used. Generators that rely on permanent magnets are sometimes called magnetos or permanent magnet synchronous generators (PMSGs).

- Armature: This is the power-producing component where the electric current is actually generated. It consists of windings (coils of wire) where the magnetic field's movement induces an electric current. Crucially, the armature can be located on either the rotor or the stator, depending on the generator's design.

A Boost of Power: Understanding Self-Excitation

Imagine a generator that can give itself a power boost. That's essentially what self-excitation is. This clever concept involves diverting a small amount of the generator's own output power back to its electromagnetic field coils. This feedback loop significantly amplifies power production.

How does it start? Even after a generator has been turned off, a tiny bit of residual magnetism (remanent magnetism) often remains in its metallic components. When the generator first starts spinning, this remanent magnetism induces a small current. This small current then flows to the field coils, which in turn creates a slightly larger magnetic field. This larger field induces an even larger current, and the process rapidly escalates until the generator reaches its steady, intended output. Large power station generators, especially after widespread power outages (a "black start"), might even use a separate, smaller generator to provide the initial excitation current.

DC vs. AC: The Two Main Types of Generators

When we talk about electromagnetic generators, they generally fall into two main categories, defined by the type of current they produce:

- Dynamos: These generators produce pulsing direct current (DC). They achieve this using a commutator, a mechanical switch that periodically reverses the direction of the current to ensure it flows in one direction to the external circuit.

- Alternators: These are the workhorses of modern power grids, generating alternating current (AC). Unlike dynamos, alternators do not use a commutator, allowing the current to naturally alternate direction as the rotor spins.

While dynamos were crucial in the early days of electrification, alternators, with their ability to easily change voltage levels and transmit power efficiently over long distances, eventually became the dominant form of power generation for our interconnected grids. If you're looking for more details on the general concept, you might want to explore what is a generator? in a broader sense.

Beyond the Basics: Specialized Generator Designs

While dynamos and alternators cover the vast majority of electric power generation, the world of generators is rich with specialized designs tailored for unique applications.

Homopolar Generators: Low Voltage, High Current

Imagine a simple spinning disc or cylinder. A homopolar generator works by rotating a conductive disc or cylinder perpendicular to a uniform static magnetic field. This simple setup creates a potential difference between the center and the rim of the disc. While they produce very low voltage, homopolar generators can generate truly tremendous currents—often exceeding a million amperes—due to their incredibly low internal resistance.

MHD Generators: Power from Hot Gas

Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) generators are a fascinating type that directly extract electric power from moving hot gases (plasma) through a magnetic field, all without the need for rotating machinery. This technology emerged in the mid-20th century, with notable advancements like the AVCO Mk. 25 developed in 1965 and the Soviet U 25, which operated at a remarkable 25 MW from 1972. They offer a unique approach to power generation, especially for high-temperature applications.

Induction Generators: Versatile Energy Recovery

You might be surprised to learn that an AC motor can also function as a generator. When an AC motor's rotor is mechanically turned faster than its synchronous speed, it becomes an induction generator. These are incredibly useful in applications like minihydro plants, wind turbines, and even for recovering energy from high-pressure gas streams. They offer energy recovery with simple controls and can operate at grid frequency without needing complex speed governors.

Linear Generators: Simple Motion, Complex Power

Forget rotational motion; linear electric generators produce current from a sliding magnet moving through a solenoid. This simple principle makes them ideal for compact and specialized uses, such as in Faraday flashlights, where shaking the device generates power, or in wave power systems, harnessing the up-and-down motion of the ocean.

Variable-Speed, Constant-Frequency Generators: Adapting to Conditions

In situations where the prime mover's speed (the source of mechanical power) can't be perfectly regulated – like in a wind turbine where wind speeds fluctuate – variable-speed constant-frequency generators come into play. These systems often use doubly fed electric machines or standard generators combined with rectifiers and converters. This allows them to regulate the output frequency over a wide range of shaft speeds, significantly improving energy production efficiency.

Where Do Generators Power Our Lives? Real-World Applications

From massive power plants that light up entire regions to tiny hand-cranked devices, electric generators are truly everywhere.

Powering the Grid: Utility-Scale Generation

The most impactful application of generators is in power stations. These industrial facilities are home to colossal generators that convert mechanical power into three-phase electrical power, ready for distribution across our grids. These giants are driven by a variety of energy sources:

- Fossil Fuels: Coal, natural gas, and oil are burned to heat water, creating steam that spins turbines.

- Nuclear Power: Nuclear fission generates heat to produce steam, just like fossil fuels.

- Renewables: Wind turbines harness the kinetic energy of wind, hydroelectric dams convert the force of falling water, and even solar thermal plants concentrate sunlight to create steam.

On the Go: Vehicular and Portable Power

Generators aren't just for stationary power plants; they're vital for mobility too:

- Roadway Vehicles: Most cars and trucks use alternators to generate electricity while the engine is running, charging the battery and powering accessories. (Historically, DC dynamos were used).

- Bicycles: Small bottle or hub dynamos (which are actually tiny permanent-magnet alternators) power bicycle lights. Electric bicycles even use regenerative braking, turning the motor into a generator to recharge the battery as you slow down.

- Sailboats: These often employ water- or wind-powered generators to keep onboard batteries charged for navigation and living essentials.

- Recreational Vehicles (RVs): Many RVs have onboard generators (gensets) to power appliances and accessories when disconnected from shore power.

Backup and Beyond: Gensets for Every Need

When the grid goes down, gensets often come to the rescue. An engine-generator set (genset) combines a generator with an engine (ranging from small petrol engines to large industrial turbines) to provide independent and backup power. These are indispensable for hospitals, data centers, construction sites, and homes during power outages.

Human Ingenuity: Powering with Muscle

Sometimes, the most reliable power source is human effort. Human-powered electrical generators are driven by muscle power. Think of hand cranks used for field radios or emergency chargers, or pedal power systems for charging batteries in off-grid situations. An average healthy human can produce around 75 watts for eight hours, while a first-class athlete can achieve around 298 watts for the same period (though this would exhaust an average person in just 10 minutes!).

Precise Measurements: Tachogenerators

Generators can even be used for precise measurement. Tachogenerators are specialized electromechanical devices that produce an output voltage directly proportional to their shaft speed. This makes them invaluable for speed indication, control systems, and ensuring machinery operates within desired parameters.

Keeping Your Power Running Smoothly: Essential Generator Maintenance

Whether it's for emergency backup or regular use, proper generator maintenance is not just about longevity; it's about ensuring safety and optimal performance when you need it most. Regular tasks like inspection, cleaning, lubrication, parts replacement, and test runs are crucial.

The Basics: Why Maintenance Matters

A well-maintained generator is a reliable generator. Neglecting maintenance can lead to reduced fuel efficiency, premature wear and tear, and, most critically, failure to start when an emergency strikes. Think of it as preventative care for your power source.

Filter Fundamentals: Air and Oil

Two of the most important filters in your generator's engine are:

- Air Filters: These are your generator's first line of defense against dirt, dust, and other contaminants. By preventing these particles from entering the engine, air filters maintain fuel efficiency and significantly reduce wear on internal components. It's generally recommended to change air filters every 350-450 hours of operation.

- Oil Filters: Just like in your car, oil filters remove contaminants from the engine oil. Clean oil is vital for lubricating moving parts, reducing friction, and extending the life of your engine. Plan to change oil filters every 150-200 hours.

Changing Filters: A Quick How-To

Always ensure your generator is completely off and cooled before starting any maintenance. Locate the filter housing, carefully remove the cover and the old filter element, and replace it with a new, manufacturer-recommended filter. Once done, perform a test run to ensure everything is functioning correctly.

Troubleshooting 101: When Your Generator Won't Start

A generator that won't start is a common and frustrating problem. Here are a few quick checks:

- Low Fuel: This might seem obvious, but it's often overlooked. Ensure your fuel tank has enough fuel for operation.

- Battery Issues: For electric-start generators, a dead or weak battery is a frequent culprit. Check the battery terminals for corrosion, clean them if necessary, and try a jump-start or recharge. If the battery is old, it might need replacement.

- Leaks or Weak Electrical Connections: Visually inspect for any obvious fuel or oil leaks. Also, check all electrical connections, especially those to the battery and starter, ensuring they are clean and tight.

For more detailed guidance, exploring essential generator maintenance tips can save you a lot of headache and expense down the road.

Choosing Your Powerhouse: Key Generator Specifications to Consider

If you're in the market for a generator, navigating the various options can be daunting. Understanding the key specifications will help you make an informed decision that perfectly matches your needs.

Matching Power to Your Needs: Kilowatts are Key

The most critical specification is power output, typically measured in kilowatts (kW). Before purchasing, calculate the total power requirements of the appliances and tools you intend to run simultaneously. It's always wise to err on the side of caution and choose a generator with a slightly higher output than your calculated maximum load to prevent overloading.

Fueling Your Future: Gas, Diesel, Propane, Solar

Generators come in various fuel types, each with its own set of benefits and drawbacks:

- Gasoline: Common for portable, smaller generators. Pros: readily available, easier to start in cold weather. Cons: shorter shelf life, higher fuel consumption than diesel for the same output, more flammable.

- Diesel: Preferred for larger, industrial, and heavy-duty generators. Pros: more fuel-efficient, longer engine life, safer (less flammable than gasoline). Cons: louder, higher upfront cost, can be harder to start in extreme cold.

- Propane: Often used for standby generators. Pros: clean burning, longer shelf life, can be stored indefinitely in tanks, flexible for dual-fuel systems. Cons: slightly less fuel-efficient than gasoline or diesel, tanks need to be refilled or replaced.

- Solar: Increasingly popular for silent, emission-free power. Pros: renewable, quiet, no fuel costs. Cons: dependent on sunlight, higher upfront cost for panels and batteries, lower continuous output than traditional fueled generators.

Your choice of fuel will impact everything from operating costs and convenience to environmental footprint. For detailed comparisons, understanding how to choose the right generator based on fuel type is crucial.

Engine Deep Dive: Horsepower, Cooling, Displacement

The engine is the heart of your generator, and its specifications provide insight into performance and durability:

- Horsepower (HP): A measure of the engine's power. Higher horsepower generally means a more capable engine, but it also correlates with fuel consumption.

- Cooling Type:

- Air-cooled: Common in smaller, portable generators. They are compact, lighter, and simpler but tend to be louder and less suitable for continuous, heavy-duty operation.

- Liquid-cooled: Found in larger, standby, and industrial generators. They offer superior cooling, quieter operation, and significantly greater durability and longevity, ideal for continuous use.

- Displacement: Measured in cubic centimeters (cc), this indicates the total volume swept by the pistons in the engine's cylinders. Generally, a larger displacement engine can produce more power, but also consumes more fuel.

Empowering Your Understanding of Electrical Power

From the ingenious spark of Michael Faraday to the sprawling power grids that define our modern world, the electric generator stands as a testament to human innovation. Understanding what is an electric generator? isn't just about technical specifications; it's about appreciating the silent, tireless machines that enable our digital lives, keep our food fresh, and light our way through the darkest nights.

By grasping the basics of how these powerhouses convert mechanical energy into electrical current, the different types available, and the importance of their maintenance, you're not just gaining knowledge – you're empowering yourself with a deeper appreciation for the energy that fuels our world.